The Thai King: Cult Hero Of The 21st Century?

I have lived in Thailand for three years but, some days, I don’t understand this country at all.

I can’t understand the ‘don’t worry about it’ attitude that you’re faced with any time there’s a worrying situation, the apparent ambivalence towards seatbelts despite the country’s appalling road death statistics, not to mention the apparent ease they have with the number of attempted military coups their government boasts — 21 at the last count.

But the one thing I can understand — or at least recognise — is the Thai’s attitude towards their late King, Bhumibol Adulyadej.

I’ve seen the reverence, the funerary ritual, the belief in his immortalisation all before.

I’ve seen it in Ancient Greek hero cult.

Both Thailand and Ancient Greece have their own complex, opaque and multi-layered, individual cultures.

But nothing truly stands alone in this world: there are glimmers of reflection in these seemingly completely divergent civilisations — glimmers from the ancient world that help us to understand the world we’re living in right now.

Or, at least, the world I’m living in.

Word on the street is that there aren’t too many classicists hanging out in the wilds of Southeast Asia. To their detriment, I imagine.

What is Ancient Greek Hero Cult?

The Ancient Greek cult heroes overshadow even Marvel’s pantheon when it comes to fame and glory.

Hailing from the titular Heroic Age, you’ve likely seen this cast of characters before.

Here are a few of the most famous:

- Achilles

- Odysseus

- Heracles

These were men from myth and legend who the Ancient Greeks heard about and learned about in their literature and oral culture, who lived to perform heroic deeds and died in pursuit of them.

Their entire reason for living was to achieve kleos amphthiton, or unwilting glory. So unwilting was their kleos, that we’re still talking about it now, millenia after the fact.

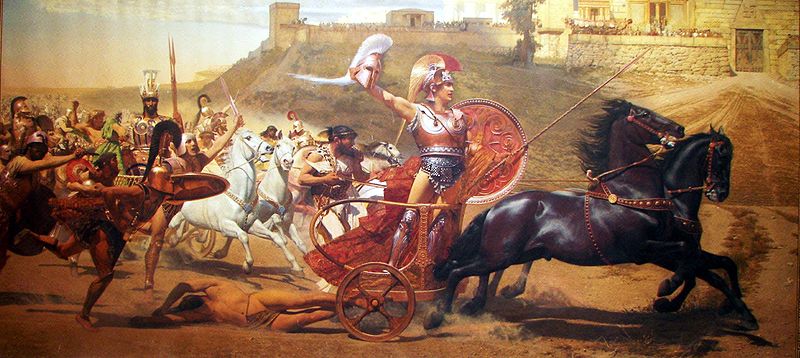

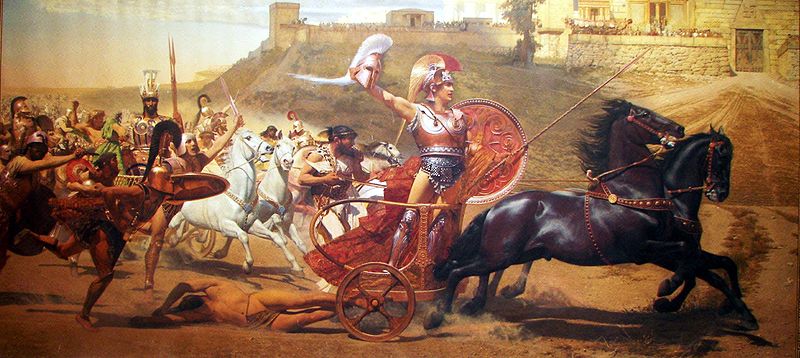

Achilles captured it best:

If I stay here and fight at the walls of the city of the Trojans, then my safe homecoming will be destroyed for me, but I will have a glory that is imperishable.

Iliad IX 412-414

They lived and died for the kleos. They were immortalised for all eternity by creators like Homer, Sappho, Sophocles and Aeschylus who put down their deeds in verse.

But what’s significant about these heroes isn’t only what they got up to in their own lives — but how they were received and perceived long after their deaths by the people of Ancient Greece. Specifically, in the cults that spread out around them.

Their tombs became sites of pilgrimage and ritual for worshippers from all around Ancient Greece.

Achilles, whom legend has it was born in Thessaly, reportedly had a tomb found on the Asia Minor side of the Hellespont. This site was visited by the Thessalians regularly with some ritual, according to Philostratus:

When they approached the tomb after the hymn, a shield was banged upon as in battle, and together with rhythmic coordination they cried alala while calling upon Achilles. When they had garlanded the summit of the tumulus and dug sacrificial pits on it, they slaughtered the black bull as to one who is dead.”

Heroikos, 53.11-12

Homer’s Odyssey too points delicately to the hero cult that will eventually be bestowed upon the hero:

Next, over these [= the bones of Achilles and Patroklos], a great and faultless tomb

Was built by us the sacred band of Argive spearmen

On a promontory jutting out over the vast Hellespont,

So that it might be visible, shining forth from afar, for men at sea,

Both for those who live now and for those who will live in the future.Odyssey, XXIV 80-84

The Immortalisation Question

According to classical linguist Gregory Nagy, the core feature of Ancient Greek hero cult was the idea that the hero would be immortalised after death.

To show that King Bhumibol is a model of an Ancient Greek cult hero in 21st century Thailand, we would need to prove that there is an underlying belief in his immortalisation following his death.

The first, perhaps obvious, point to note is that Bhumibol — like all the cult heroes of Ancient Greece — was human and died a mortal death.

Just as the legend goes that Achilles died from a bow shot at his ankle, so we know that Bhumibol died after a long illness culminating in kidney failure.

The immortalisation part comes after the death.

There are a few sources for Achilles’ post death immortalisation and it was even hinted at by Homer, who was notoriously opaque about such mystical possibilities.

In the Odyssey, the spirit of Agamemnon details the burial rites of Achilles, to whose spirit he is now talking to in Hades:

we gathered your white bones at dawn, O Achilles, and laid them

In unmixed wine and in oil. Your mother gave

A golden amphora to hold them – she had received it as a gift from DionysusOdyssey, XXIV 72-75

This golden amphora provided by Thetis, Achilles’ mother, via the god Dionysus, is an indicator of the hero’s future immortality.

When Achilles’ bones were added to the amphora, which already held the cremated remains of his best friend Patroclus, they would be transformed back into life thanks to the regenerative power of Dionysus, who has long been associated with rebirth and immortality.

The Tomb

We have no Thai epic poems to illustrate belief in King Bhumibol’s possible immortality, but there are plenty of hints that his funeral was stage managed in order to best guarantee his passage into the afterlife.

His crematorium in the centre of Bangkok’s old city had a number of features that can certainly be seen as a tomb fit for a cult hero.

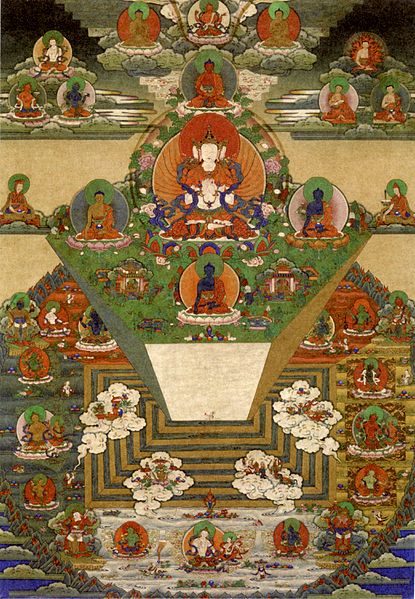

The design of the golden 9-spire structure itself was based on Mount Meru — the cosmic and spiritual centre of the Hindu universe.

Thailand is Buddhist, but Hinduism and even a Hellenic-esque animism have permeated and shaped the Thais’ relationships with faith and mortality.

Mount Meru was the home of Brahma, a creator god in both Buddhism and Hinduism.

Reincarnation is an important tenet of these religions’ beliefs. Brahma is a leading god who presides over the most desired celestial realm of rebirth — the Brahmaloka.

To be reincarnated within the Brahmalokha would give King Bhumibol the status that many other cultures — including Ancient Greece — would regard as divine immortalisation. Brahmas can visit earth and influence human affairs — just like our cult heroes did in Ancient Greece.

Let’s take a look at Protesilaos, for instance, another Thessalian cult hero who died in the Trojan War.

According to Philostratus, there was once a beautiful garden, said to be the sacred space of Protesilaos: a place he regularly visited when he returned from the afterlife.

It was tended by a gardener, known in Greek as the Ampelourgos.

The Ampelourgos described Protesilaos’ regular reincarnations to a Phoenician visitor:

{Ampelourgos} “…We work the land together.”

{Phoenician} “Has he come back to life, or what?”

{Ampelourgos} “He himself does not speak about his own experiences, stranger, except, of course, that he died at Troy because of Helen, but then came to life in Phthia because he loved Laodemeia.”Heroikos, 2.8-2.10

Will King Bhumibol be immortalised and have the ability to walk among his people once more?

Regardless of my own personal convictions, I think the answer here is that the Thai people absolutely believe that he will.

Heroic Reception: Thailand vs Ancient Greece

Beyond the fact that Thai people so clearly adore their late king, it’s clear on the ground that they think of him as so much more than just a man.

Just like the Ancient Greek heroes who were lauded in epic and lyric for their heroic actions and deeds, the Thais ascribed to Bhumibol an almost demigod status.

Heroic Deeds

To be an Ancient Greek cult hero was to have performed incredible feats of strength, mental agility and all-round larger than life actions.

Heracles, for instance, performed his 12 labours in order to atone for the murder of his wife and son:

- Kill the Nemean lion

- Kill the Lernaean Hydra

- Capture the Ceryneian Hind

- Capture the Erymanthian boar

- Clean the Augean stables in a record 1 day

- Kill the Stymphalian birds

- Capture the Cretan bull, father of the Minotaur

- Capture the mares of Diomedes

- Steal the girdle of Hippolyta

- Steal the cattle of Geryon

- Steal the apples of the Hesperides

- Capture three-headed dog Cerberus and bring him back from Hades

Achilles was known as ‘the best of the Achaeans’, the strongest warrior the world had ever known. So elevated was his prowess on the battlefield that his short hiatus from the Trojan War was enough to put the glory of the Achaean side in doubt.

Odysseus is known as a warrior, but rather for his agile, problem-solving mind — a mind so seasoned that it kept him alive during the decade it took to return home to Ithaca from Troy and, of course, pioneered the stratagem that allowed the Achaeans to sack the fallen city in the first place: the Trojan horse.

Bhumibol doesn’t have quite the same violent flavour of heroic deeds rounding out his CV.

It’s a different time, after all.

But to bastardise The Dark Knight, Bhumibol was the hero that Thailand needed, if not the one it deserved.

Reigning for an impressive 70 years, his years on the throne saw Bangkok transform from an oriental backwater to the cosmopolitan centre it is today.

This country’s political landscape is more fractured than Evel Knievel but Bhumibol was always the one stabilising influence that the country clung to, the pillar of certainty as the political establishment crumbled around him.

He mended fences between factions, brought riots to their end, all with the calm and erudite air missing in Thailand’s dirty politics.

Even now, almost 18 months after his death, images of the King’s good deeds are everywhere.

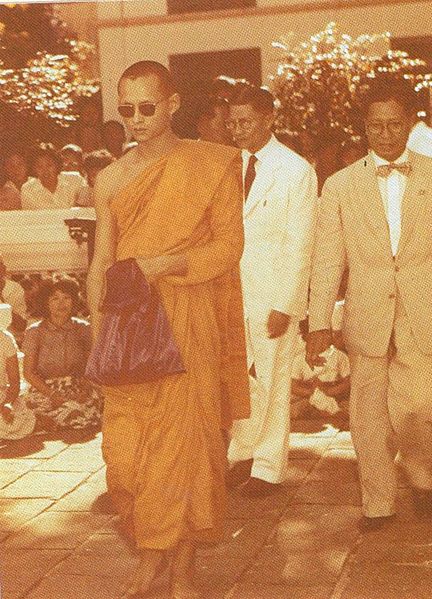

We see him tending to his people, talking with children and blessing those who come out to see him. Before every film that rolls at every cinema throughout the land, there plays a short reel of images and video of Bhumibol accompanied by the royal anthem.

Every image that the Thais see and have seen of Bhumibol have been engineered to show him as their hero.

Heroic Character

There’s a very famous part of the Iliad which speaks obliquely to the subject of heroic character.

What makes a hero?

During the funeral games for Patroclus, it’s announced that there will be a chariot race featuring heroes such as Diomedes, Menelaus and Antilokhos, the son of Nestor.

Nestor offers his son advice about how to best drive the chariot in order to win the race. He is speaking about the steps Antilokhos should take when he approaches a particular turning post, known in Greek as a sema, which can also refer to the tomb of a hero:

Get as close to it as you can when you drive your chariot horses toward it,

And keep leaning toward one side as you stand on the platform of your well-built chariot,

Leaning to the left as you drive your horses. Your right-side horse

You must goad, calling out to it and give that horse some slack as you hold its reins

While you make your left-side horse get as close as possible,

So that the hub will seem to be almost grazing the post

– The hub of your well-made chariot wheel. But be careful not to touch the stone,

Or else you will get your horses hurt badly and break your chariot in pieces.Iliad XXIII 334-342

Nestor here is emphasising the balance necessary for a heroic win — impulse and restraint.

Knowing when to push yourself forward and when to hold back is the key to achieving the kleos amphthiton that our cult heroes so desired.

Achilles practiced it when he withdrew to his tents after being besmirched by Agamemnon at the start of the Iliad, before throwing himself back into the nexus of the action and killing Hector following the death of Patroclus.

Odysseus was the master of balancing impulse with restraint: we see this quite literally played out during Book 12 of the Odyssey when he and his crew sail toward the island of the Sirens.

The Sirens were creatures who would sing incredibly beautiful songs that revealed deep truths about the future. So enchanting were these tunes that any man who heard them would never leave their island, resulting in their eventual death.

Thirsting for knowledge, Odysseus used his heroic character to both hear the truth of the Sirens’ song, while keeping himself safe and able to move forward.

He plugged the ears of his crew with wax and ordered them to bind him tightly to the mast of the ship as they passed the formidable island. Restraint — with a dash of impulse in the genesis of the idea.

While there are none of these colorful tales in relation to King Bhumibol — at least not for public consumption — he was undisputedly a model of kingly balance, who used impulse and restraint to great effect in order to benefit the people of Thailand.

Salacious stories have always swarmed around royal families — certainly in the UK and equally so in Thailand. Even though the media has been restricted in what they can report in Thailand, Thais are well aware of the stories that circulate beyond the firewall.

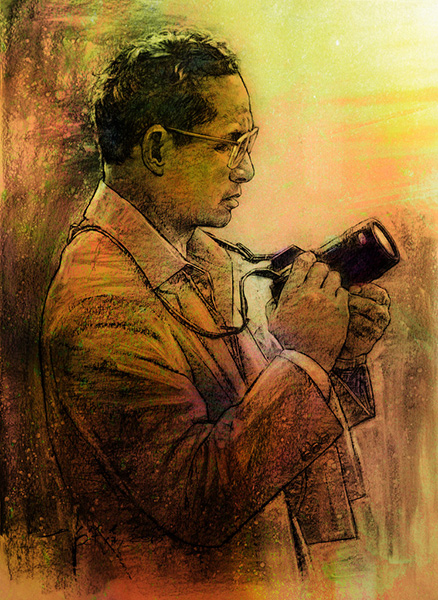

But none of these stories have ever been in reference to the late king — he was the picture of balance, a family man, a man of the people, a man with hobbies — jazz saxophone and photography no less — and a man who knew that wielding his immeasurable power was a weapon best used sparingly.

1992, for instance: the only year he publicly intervened between military and political factions in order to force a peaceful resolution following yet another bloody coup. Perhaps as a direct result of this rare display of arbitration, Thailand shortly afterward held a general election leading to a democratic civilian government.

King Bhumibol’s Death

One of the most striking aspects of Thai culture is the reverence that they pay to their royal family. And none more so than to the late King himself.

When he died, it was akin to the passing of a beloved father.

In the days leading up to his death, crowds gathered outside the hospital he was staying at, sobbing and clutching their amulets in a bid to summon luck for his health.

When the death announcement was made, Bangkok was painted black.

And not just our wardrobes: TV screens, Facebook profiles, even global websites were taken down to grey scale.

The body was transported in a huge autocade to Bangkok’s Grand Palace a day following the death, where he was given bathing rites before lying in state for a full year. The first 100 days after his death saw daily rites performed upon the body, in order to guarantee his ascension into the afterlife.

During the year that he lay in state, where he was attended by a monumental 12 million well wishers, the government was hard at work constructing his tomb — referred to as the royal crematorium.

He was cremated on October 26 2017, just over a year following his death, and the crematorium was dismantled at the end of 2017.

Hero Worship: Ancient Greece vs Thailand

Some Thai people might contest that they ‘worship’ the late King Bhumibol.

But the honours they paid to him — both in life and after death — resemble closely the worship of cult heroes in the world of Ancient Greece.

Thailand is a spiritual place. Spirit houses abound the streets, a notable feature outside every building.

These small shrines are created in order to provide shelter to the spirits that live among us. Members of the household will leave votive offerings daily in the spirit houses in order to appease their ghostly visitors.

Commonly seen votives include incense, sticky rice, crafts and, quite curiously, bottles of red Fanta.

I first assumed that the Fanta was put there to symbolise blood, but have learned that it was King Bhumibol’s favourite beverage. The people of Thailand present their spirit houses with red Fanta regularly to soothe the spirit of King Bhumibol.

Offerings have been found for specific cult heroes in the Ancient Greek world too.

Take the Menelaion, for instance, a hero shrine found near Sparta where votive offerings were left for Menelaus and his wife, Helen.

These mostly included lead placards honouring Menelaus, as well as an assortment of ornate offerings depicting images of horses and exotic animals.

Meanwhile, spotted at a spirit house in Bangkok…

Funerary Rites

Both Thailand and Ancient Greece place great emphasis on the ritual preparation of the body and the burial/cremation itself.

King Bhumibol’s initial bathing rites were broadcast live on TV and personally carried out by his son, the now King Vajiralongkorn.

Bathing rites are nothing new in funerary ritual in many world cultures. What notches up Bhumibol’s was the fact that the general public of Thailand were invited to take part in symbolic bathing rites of their late king in front of a huge portrait — symbolic of a larger-than-life hero — nearby where he lay in state.

The entire community worked together in order to prepare the body for the afterlife.

Lycian cult hero Sarpedon was already predicting the burial rites his community would lavish upon him after his inevitable demise at Troy:

And there [=in Lycia] his relatives and comrades will ritually prepare him,

With a tomb and a stele — for that is the privilege of the dead.Iliad, XVI 456-457

For the Ancient Greeks, having a burial was mandatory to guarantee a successful passing into the afterlife.

Homer is especially emphatic on this point, as we see from his portrait of the spirit of Patroclus, visiting Achilles after his death:

Bury me with all speed that I may pass through the gates of Hades.

Keeping me away from there are the spirits, who are images of men who have ended their struggles;

They are not yet permitting me to join them beyond the river.Iliad XXIII 71-74

The river Patroclus mentions here is the Acheron. This is the river that Charon ferries the spirits of the buried dead across at the gates of Hades, symbolising their crossing from the land of the living into the land of the dead.

While a speedy burial clearly wasn’t the number one priority when it came to Bhumibol, there was a clear emphasis on getting everything right so the King could ascend into the afterlife.

Prolonged rites, an involved community, an incredibly symbolic tomb.

All ingredients to be admitted into the Brahmalokha.

When is a Cult No Longer a Cult?

While figures like Achilles, Herakles and Odysseus were pan-Hellenic figures worshipped in various locations around the Ancient Greek world, they were still very much cult heroes.

What do we mean by that?

Essentially, that certain places claimed them as their own and had their own rituals in place to worship them.

Here are a few of the centres of Achilles’ cult worship, for instance:

- Thessaly

- Astypalaea in the Sporades

- Sparta

- Elis

- Tarentum

- Locri

- Croton

We don’t have that with Bhumibol.

Sure, there are a few anti-royalists in Thailand, but this is not a local cult — or series of local cults — like we see occurred with the Ancient Greek heroes.

This is a Thailand-wide cult.

And arguably even wider than that owing to the Thai diaspora.

But I think we can argue that Bhumibol still qualifies as a modern development of the traditional cult hero. It’s just that the size of his cult is on a different scale to those from Ancient Greece.

This is due to 3 factors: status, image and time.

Status: King vs Hero

While we’re equating Bhumibol’s image with that of the Ancient Greek cult heroes, the fact is that he is a recently deceased monarch of a country with a population just dipping below 70 million.

Of course, some of the Ancient Greeks were kings too — Odysseus was King of Ithaca — but the kingdoms they oversaw were small and, compared to modern day Thailand, relatively inconsequential.

They simply didn’t have the same reach.

Image: The Power of the Media

Another determining factor to the size of these cult heroes was how widely their stories were circulated.

The mythology of the Greek cult heroes were widely disseminated for their day — oral culture and vase paintings had fully penetrated the region to the extent that the heroes’ stories were known far and wide — but this can in no way compare to the reach of the media in the 21st Century.

In Thailand, images of the royal family are everywhere — hanging down 100ft skyscrapers, in every home, restaurant and street food stand, in a short film before a cinema screening, you name it.

The fact is that Bhumibol’s image is much wider known than the cult heroes of Ancient Greece ever were.

Time: Kleos Amphthiton

The final factor in the size of the cult is how long after the event they were established.

King Bhumibol has only been buried for a few months at the time of writing: there’s no way of knowing what his hero cult might look like in 5 years, 50 years, 100 years and 500 years.

Will it have reduced? Probably. Will he still be ‘worshipped’ in certain parts of Thailand? I wouldn’t be surprised.

Bhumibol: Modern Day Cult Hero?

Considering the apparent massive divergency of their cultures, I think that there are a surprising number of features that the Ancient Greek cult heroes had in common with the late King Bhumibol of Thailand.

Of course, this is all academic: such reflective coincidences as these can be found in a multitude of cultures, over a number of different time periods.

If anything, our little experiment here underlines the incredible importance that both Ancient Greece and Thailand place on the mythology of their local heroes, and the ritual they attach to ensuring passage into the afterlife.

But I think Thailand’s curious attachment to the late, great Bhumibol can be understood so much easier and more fully if we view him through the lens of the cult heroes of the Ancient Greek world.